- 6:30pm Wed, Mar 29:

- Presanctified Liturgy

- 6:30pm Thu, Mar 30:

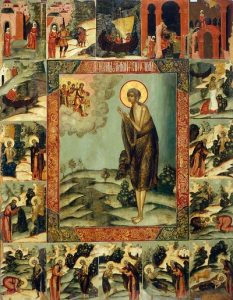

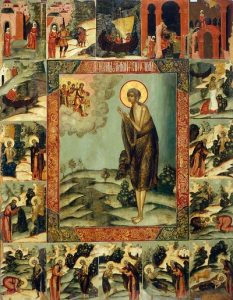

- Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete (complete) with the Life of St. Mary of Egypt

St. John of Shanghai Orthodox Church

The English-language Orthodox Church in Vancouver, BC

The Feast of the Annunciation, falling in the middle of our Lenten struggle, reminds us that purity and holiness are not only possible, but also practical and powerful.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

On the third Sunday of Great Lent, we venerate the Holy Cross of our Lord (more on that here), and our attention is drawn in the prescribed readings to shame (Mark 8:34-9:1) and weakness (Hebrews 4:15-5:6) and to the transformative and redemptive power of following our Lord by taking up our own cross in order to become true followers of Him.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Meditations on how the Church, like the Ark, helps to save us. We still need to stay in the boat, by living within the Way of Life that our spiritual forefathers received from God and built for us, but, as we do so, we find that we are not blown every which way by every wind and wave of doctrine: we find stability of life and thought as we grow up together into Him who is our Head.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

In catechumen class today my attention was drawn to “The Dream of the Rood“, one of the oldest extant works of Old English literature which I’m sure I’ve read about at some point in my study of English literature, but which I’d never actually read. So, when I found a modern English translation of it online, I read it, and was struck by both its beauty and by the way it addresses the cross directly, just as does our own “Akathist to the Spiritual Ladder, the Precious Cross“.

In fact, while I haven’t thoroughly analyzed the theology of “The Dream of the Rood”, I actually found I preferred it to “our” akathist (I put “our” in quotation marks here because, given the very pre-schism date of “The Dream of the Rood”, it potentially has just as much claim to being part of our tradition as the Akathist does), mainly because where the Akathist stays true to form and calls upon the cross to rejoice (as is common to the refrain in all akathists), “The Dream of the Rood” portrays the cross as having a much more nuanced and conflicted view of its having become the means of our Lord’s victory over sin and death on our behalf:

In fact, while I haven’t thoroughly analyzed the theology of “The Dream of the Rood”, I actually found I preferred it to “our” akathist (I put “our” in quotation marks here because, given the very pre-schism date of “The Dream of the Rood”, it potentially has just as much claim to being part of our tradition as the Akathist does), mainly because where the Akathist stays true to form and calls upon the cross to rejoice (as is common to the refrain in all akathists), “The Dream of the Rood” portrays the cross as having a much more nuanced and conflicted view of its having become the means of our Lord’s victory over sin and death on our behalf:

Then I saw mankind’s Lord come with great courage when he would mount on me. Then dared I not against the Lord’s word bend or break, when I saw earth’s fields shake. All fiends I could have felled, but I stood fast.

The common theme here of addressing an inanimate object (as Paul does when he exclaims, “O grave, where is your victory?”) ties into what we noted in today’s sermon, in that, as followers of Christ, we can no longer consider the cross apart from what our Lord accomplished on it – and it is this that transforms it, for us, from a terrible instrument of torture into the very means of our salvation. It is as we take up our own cross daily and follow Christ that we are working out our own salvation in fear and trembling, and it is this inextricable association between the cross and what Christ accomplished by it that elicits our response to honour it and even to embrace it as the ultimate symbol of our Lord’s (and, by association, of our own) ultimate triumph over sin and death.

As the Akathist says,

Seeing the strange wonder, let us live our life as strangers, lifting our minds up to heaven, for this reason was Christ affixed to the Cross, and suffered in the flesh having willed to draw to the heights them that cry to it: Alleluia!